Highlighting Australia

- As a proudly Australian initiative, we’re excited to showcase a collection of Australian stories, music, tributes and more.

Join activities, celebrations, study groups, spiritual empowerment and education programs for young people, and more.

Baha’i beliefs address essential spiritual themes for humanity’s collective and individual advancement. Learn more about these and more.

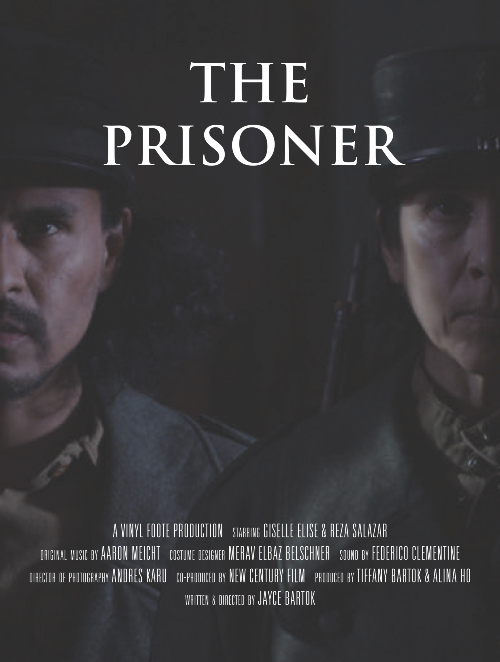

Inspired by the early history of the Baha’i Faith, The Prisoner is a new short film by writer and director Jayce Bartok. Set in the 1800s, the film imagines a conversation between two bickering prison guards at the fortress of Chihriq in north-western Iran where the prophet known as the Bab was imprisoned, and where He revealed some of His most notable Writings. The Bab’s message caused a revolution throughout Persia and the two prison guards, each harboring a difficult secret, connect with one another while keeping watch over the Bab. Ultimately this short film is about finding faith in unexpected moments.

I caught up with Jayce Bartok to find out more about The Prisoner and the inspiration behind it.

Naysan, so nice to get to chat. Yes, The Prisoner is a short film about two prison guards bickering away as they watch over a prophet…not your usual short film subject matter! It’s set in the 19th century, and is, for lack of a better word, historical fiction. The backdrop of the script is based on the life of the Bab, a Prophet of the Baha’i Faith, who created a spiritual revolution across Persia of the 1800s. For those who don’t know, the Bab’s followers, known as the Babis, were being executed and imprisoned for this spiritual revolution – as the Bab Himself was imprisoned for the last years of His life then executed by a firing squad at the age of 30. It’s a very powerful story to tell, a daunting one, so I wrote these fictional prison guards as a way into our understanding of the Bab at a time right before His execution. In a manner of speaking, they are learning about the Bab along with the audience. The guards are written to be very human, flawed even – one is very macho, full of bluster on the surface, but you begin to learn he has a sensitivity underneath, especially about his daughter. His name is Abbas and he is played by Reza Salazar, a terrific actor here in New York City. The other guard, Ghazi, is a woman “passing” as man, played by Giselle Elise, another very gifted actor. Ghazi’s character, who harbors this dangerous secret, allows the piece to grapple with lots of issues of equality that were very forbidden in that time period without hitting the viewer over the head or seeming to be anachronistic. I hope I said that right! Equality is a huge principle of the Baha’i Faith and something these two guards are unfamiliar with, but it’s the basis of their connection. They tease each other, taunt, argue over who will get to eat the Bab’s uneaten food as He is on a hunger strike, all the while processing what they have witnessed – the Bab’s impact on the community – and what will happen to Him (His rumored execution). The theme of the piece is about connection with one another in the most unlikely of places between two people who couldn’t be more different and who don’t consider themselves believers in any way!

Good question. Well, my friend and collaborator on this, Aeric Meredith-Goujon, was on the Holy Day Committee for the New York City Baha’i Community. Full disclosure – I am a Baha’i which you probably knew. Aeric called me one day, pre-pandemic, it was the summer of 2019, and said, “Listen, for the Birth of the Bab celebration in October, I want to do something different. I am reaching out to artists in the community, and we have a super small budget to commission pieces of art for the celebration… that are different in tone than the normal Holy Day devotions.” If you have attended a Baha’i Holy Day celebration, you know you are going to hear very beautiful songs, prayers, readings from the Writings of the Baha’i Faith… Aeric was looking for more “challenging” pieces of art, that would also attract friends of Baha’is. At first, I was like, “O.K. we will shoot an impressionistic sort of film poem’” seeing as we are filmmakers. My background is as an actor who started writing, who started directing and producing. Right off, Aeric was like, “No, we have a film already.” I didn’t have many more tricks up my sleeve. I thought, “I could write a play?” but that seems sort of conventional. Very conventional. And HARD. Also, as your readers may know, as a Baha’i you aren’t supposed to depict or show photographs or portray the Twin Prophets of the Baha’i Faith – the Bab and Baha’u’llah. Like you can’t have a historical play where someone dresses up and portrays the Bab. The reason for this, in my understanding, is to not promote iconography of the Baha’i Faith which distracts from the message of unity, equality, peace, and love. So Aeric encouraged me to work on a play, but I was stumped, man. He would call and check-in every so often throughout the summer and I started dodging his calls. I ghosted him on more than one occasion (I felt bad about that!) as I was genuinely confounded about how to approach the material, especially in a way that felt new and challenging and not like religious history. I was stressed out and hoping it would go away!

One day, I was riding the NYC subway and started thinking about the Samuel Beckett play, Waiting For Godot, in which the two main characters, Estragon and Vladimir, engage in a whole series of absurd conversations while they wait for the title character, Godot, who never shows up. At the same time, in my head popped the two criminals crucified with Jesus Christ, and this notion that these two very earthly humans who by the very nature that they are close to this Prophet, will achieve salvation. “Assuredly, I say to you, today you will be with Me in Paradise,” I believe is what Jesus tells these two common criminals. It’s a beautiful idea about redemption. Suddenly, I thought what if there were these two bone-headed prison guards stuck in their brutal lives, who are bored and hungry waiting for their shift to end and by the sheer fact that they are in proximity to this beautiful Prophet, they begin to question the existence of His authenticity and the very nature of the soul. Quickly, the one-act play took shape. After the first draft, Aeric had an amazing idea to make Ghazi “pass” as a man in the tradition of stories you hear about women pirates, women soldiers in the Civil War who had to pretend to be men to survive… This took the piece in an entirely different direction with the ability to speak about inequality, violence towards women, and the need for change in society which the Bab was all about.

Ultimately, I got to a draft that felt historically accurate and worked, and then we gave it to the Assembly of NYC to vet, so to speak. After some corrections about historical details, we started rehearsing on the small stage at the Baha’i Center on E.11th Street, and it was an AMAZING process of discovery. I wrote the play with Reza Salazar in mind, who I have known and worked with for years. I thought he would be the perfect Abbas with his combination of playfulness, sensitivity, and his ability to project a very real righteousness. And my friend Giselle – who is not a Baha’i is really the ONLY person I could ever see playing Ghazi, such a specific and difficult role – to convince the audience that you are a man, at least to let us know you are playing a man so we are in on the joke, but being convincing enough to fool your co-star. It was a delicate balance about how far to take playing “a man” with how much the piece required so it didn’t become comedic. Giselle did an amazing job. With a small budget, we were able to rent period-appropriate costumes from the Theater Development Fund Costume Library which has incredible costumes from famous Broadway shows and every era. Two years ago, actually, we performed the play over a few days – about six performances; and the reception was really encouraging. So when we closed, I was like “OK, did that, that was cool, end of story.” Little did I know others on the team had different ideas!

After the play ended, we talked about adapting the play into a short film, and had many ideas, some radical, about how to achieve that. Then the pandemic rolled in, and we all know the rest. Somewhere in October of 2020 – pre-vaccine, mind you – our cinematographer, Andres Karu, started putting out little feelers about making The Prisoner. It seemed an insurmountable task! For one: to find the funds to make the film. Moviemaking, even on the most indie budget, is very expensive. Two – um, the worldwide pandemic and the Screen Actors’ Guild rules about how to work on-set with COVID safety. Now being that both our actors are union members, we had to follow SAG’s rules which required the production to have the entire cast and crew tested within 24 hours. To accomplish this, we needed to hire a lab to turn test results around within 24 hours which would cost an additional $3,000 dollars. We also had to get our COVID Safety Plan approved by SAG and needed to hire a COVID specialist on-set to make sure all rules were being enforced. And it was all down to the wire – two days before we were supposed to shoot, SAG finally approved our safety plan.

Also, we only had the funds to shoot one day. We needed to shoot 12 pages in one day! Even on a low-budget film, you shouldn’t ever attempt more than seven pages per day. We had no choice but to try and pull it off. We had found an amazing location in upstate NY which was a former Olympic horse training facility. Under the main complex, there was a long, giant concrete room that was a former shooting range, of all things. It was there we found these amazing old wooden doors which could be our prison cell. We had revised the play into a film that felt more serious, darker, and urgent. The costumes went from being very theatrical to basically, Ottoman Turk Army uniforms that brought a realism to the facelessness of the guards. The “live” feeling of the piece on stage which would bring laughter was replaced by something almost Kafkaesque. Everyone on our creative team – our cinematographer, Andres Karu, our producers, Alina Ho and Tiffany Bartok, our costume designer, Merav Elbaz Belschner, our composer, Aaron Meicht, and even our son, Jaxon Bartok – were all excited by this new direction and we were game, pandemic or not.

We began shooting, and weathered random people trying to make set visits (a huge no no according to union rules), but as the hours wore on, we knew we wouldn’t finish within the allotted 10 hours. We had no choice but to continue and deal with overtime. The wheels finally came off during a section of the piece where the guards hear the call for morning prayer. They are both culturally Muslim, but I wouldn’t describe either as devout. It’s a transformative moment for the characters, as they wash their hands and prepare. We had done extensive research about the Morning Prayer as well as sound designing the call, we had prayer mats and beads, water bowls, and we had “blocked” the prayer. But the set came grinding to a halt when we got into the logistics of the prayer. Would it be offensive to continue to say the scripted lines during the Morning Prayer? How far to go into the ablutions would we go? Could the guards participate in Morning Prayer with their guns holstered? Would we offend people? But removing their weapons was not only time-consuming but revealing of microphones and wardrobe tape as military jackets had to be taken off. Production ground to a halt in the wee hours for about an hour or so as we debated. I was worried to say the least.

I believe that if you don’t solve a problem on set, and just cut it or hope it will go away, it haunts you in the edit room and on screen. The only way through….is through, as they say. We took the time and worked it out. The sun comes up at the end of the piece (spoiler alert) as the guards reveal their true selves to each other. I have to say that both Giselle and Reza had no choice but to be very method in their approach to the dawn in the piece. I mean, it was DAWN! I’m not sure they even knew where they were, they were so tired! Not ideal, and I have apologized profusely. Thankfully, my friends on the crew are still speaking to me. By some miracle, we wrapped, loaded out, no accidents, no COVID, and began the edit process. We shot almost one year to this day that I’m talking to you!

I hope viewers and audiences will walk away from the film feeling moved, of course. But also walk away feeling hopeful that a connection can happen between two people at any time, and in the most unexpected places if you want it, if you truly listen to each other. You can overcome your differences, or understand them, and achieve a unity, even if it’s fleeting. I feel that’s what we desperately need right now on this earth. Connection between people. Because when there is a connection, then comes change. Also, I hope audiences learn about the Baha’i Faith and want to investigate it more.

We recently screened the film for the first time at the Baha’i Center and it was so cool to hear the audiences’ reactions! The one that has stuck with me was from a woman – she was actually our last question of our Q&A – she raised her hand and said she was an atheist. But she felt a lot of spirit in this film. Most of all, she connected to the journey of the food – the chickpeas the Bab won’t eat – and how the guards are dealing with lack of food for them and their families. And how at the end, one guard gives the plate of chickpeas to the other (spoiler alert!) and instead of keeping them, he presents then to the Bab, off-screen (represented by candlelight in the cell). She said this really resonated with her. You never know what an audience will connect with! Another viewer really resonated with Ghazi passing as a man, and themes of non-binary gender issues it brings up. Giselle Elise, who plays Ghazi, sent me an article the day before we screened the film about Afghan women and the tradition that still goes on of young women passing as men especially in families that only have daughters, to get access to opportunities and standards of education that are forbidden or not available to women. I definitely think the themes in The Prisoner are ones we are still dealing with, even though this piece is set in the 19th century!

Yes, my goal is to have The Prisoner travel around the world, and I hope if you read this, and enjoy the film, please share it with someone. Word of mouth is so important. And I am really interested in what viewers take away from The Prisoner. Please comment, and let us know!

It is premiering at the Fort Lauderdale International Film Festival on Tuesday, November 9th, 12:00 PM and Thursday, November 18th, 3:00 PM at Gateway Cinema. For those in Florida, you can see it here: ‘The Prisoner’ World Premiere

Or the film can be viewed on YouTube here: The Prisoner

You can also find out more about myself and our up-coming projects here:

www.jaycebartok.com

www.vinylfoote.com

and finally, you can find me on Instagram: @jaycebartokThanks for the chat, Naysan!

"*" indicates required fields

We recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and community. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their cultures; and to elders both past and present.

The views expressed in our content reflect individual perspectives and do not represent authoritative views of the Baha’i Faith.

Visit the site of the

Australian Baha’i Community

and the Baha’i Faith Worldwide

Notifications

This looks like a very meaningful film. But, unfortunately, the sound was very bad and I could only make out some of what was said. I would love to be able to understand all of it!

Sandi Augsburger (November 11, 2021 at 4:16 PM)

Sandi,

I am so sorry you experienced that. The sound mix is normal, did you try turning up your computers volume, or raising the volume on the YouTube link?

I would love for you to be able to see and hear the film perfectly.

I can also share a link with you directly, if you’d like.

best,

Jayce Bartok

Jayce Bartok (November 11, 2021 at 9:07 PM)

Hey, I tried again and it was lots clearer this time. Maybe there was something wrong with the internet the first time I tried it!!! Now I can hear how it has so much depth and humanity in it. Thank you!!!

Sandi Augsburger (November 11, 2021 at 12:17 AM)

Thanks for giving it a second try, Sandi!

best,

Jayce

Jayce Bartok (November 11, 2021 at 2:14 PM)