Highlighting Australia

- As a proudly Australian initiative, we’re excited to showcase a collection of Australian stories, music, tributes and more.

Join activities, celebrations, study groups, spiritual empowerment and education programs for young people, and more.

Baha’i beliefs address essential spiritual themes for humanity’s collective and individual advancement. Learn more about these and more.

Featured in: Abdu'l-Baha

Abdu’l-Baha—the eldest Son of Baha’u’llah—was the Baha’i Faith’s leading exponent, renowned as a champion of social justice and an ambassador for international peace.

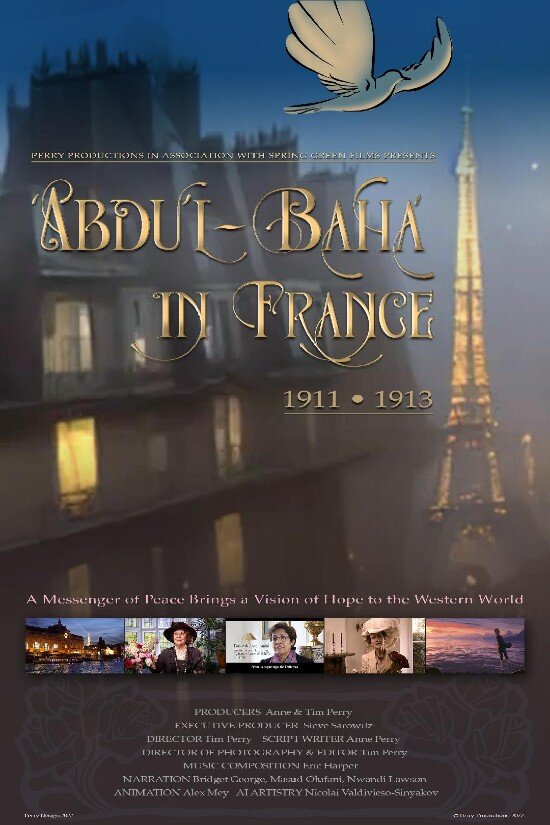

Have you seen the film Luminous Journey: Abdu’l-Baha in America, 1912? Anne and Tim Perry, of Perry Productions, have just released their latest project: a documentary called Abdu’l-Baha in France. It is a multimedia account of His sojourns in France, and through contemporary interviews, historical photographs, monologues and animations, audiences are drawn into a captivating, engaging and informative story about the incredible Personage of Abdu’l-Baha.

Anne graciously agreed to tell us all about the film and here is what she shared with us:

Could you please tell us a little about Abdu’l-Baha in France?

It’s an individual initiative project, a 90-minute documentary that tells part of the story of Abdu’l-Baha in France during His travels in 1911 and 1913—part because the story itself is such an amazing, extensive, and enthralling saga, and no work of art could present a full account of it. We worked on it for around four years, with the pandemic providing both obstacles and opportunities. And we had to trim the script considerably to make a film of a manageable length.

What inspired you to create this film?

We were initially inspired to go to Paris to see an immersive Klimt exhibit at L’Atelier des Lumières. A friend gave us tickets through her airline miles, and as we were planning our trip, we realized we should take a video camera and try to see some sites visited by Abdu’l-Baha and learn about His visits to Paris. It was only then that we got in touch with some researchers and with the National Spiritual Assembly of France, and then met with some of them while there. They were immensely helpful to our process.

Some years earlier, after we finished making Luminous Journey: Abdu’l-Baha in America, 1912, we had thought about trying to tell the larger story of His travels to Europe and Egypt, but it seemed out of reach for us, in terms of time, finances, and practicality. But when we were actually planning to go to Paris, we became excited about the possibility again. We set off on our trip with little knowledge and no script, and spent a short nine days in Paris, shooting footage of various places including the apartment where Abdu’l-Baha had stayed in 1911, which is now owned by the Baha’is and is a place of pilgrimage. We also conducted interviews with several local experts, including Jan Jasion, who had published a book on the subject.

Gradually and with the help of much research and archival material, I developed a script and we considered ways of telling the story through the narration and re-enactments paired with visual elements. I met with a script assistant, Amanda Sevak, online every week for a number of months—and then, of course, had to translate everything into French!

In 2022 we went back to France and spent eight days in Paris, three days in Thonon-les-Bains, and part of a day in Marseille. We shot more footage that we could add to the film. We also had our French version reviewed by several audiences there, who were very polite and encouraging to us, even though we had many corrections to make at that point, and have since done so.

The film includes a wonderful collage of historical photographs, contemporary footage of France, interviews, animations, and dramatic monologues. Can you tell us a bit about the process of putting all the elements of the film together?

Oh, my. It was quite a process, and so different from our work on Luminous Journey. For one thing, including interviews and contemporary footage was quite different for us, rather than making the whole film look as if it were in the past. And because we were on location for such a short time, we had to purchase some stock footage and photographs. The decision to include animation and illustration came as we got ideas about illustrating concepts that were hard (such as in the Henri Bergson scene), doing a creative title, and telling one story that we couldn’t shoot as a re-enactment. The animation was done by Alex Mey, a former student of mine who had graduated from the Art Institute of Dallas. We held weekly meetings by Zoom with our technical creative team over the course of some months.

We did most of the re-enactments at our home studio in Texas using purchased backdrops, or at Green Acre in the Sarah Farmer room and by the apple tree where Stanwood Cobb had learned of the Faith. The Lady Blomfield re-enactments were done near London with Beverley Evans Matthews, shot by Alex Kalimat. That was an amazing example of how we worked with international collaborators, many of whom we never met in person.

We also looked at a lot of art nouveau designs and French elements and ended up creating our own using Adobe Illustrator and also AI (artificial intelligence) computer-generated images. These were mostly done by Nicolai Valdievso-Sinyakov, who provided us with literally hundreds of possibilities. This added a kind of painterly look to the film in places.

We were a little afraid that the “hodge podge” method of constructing the film with its various elements would be off-putting, but response has been positive about the different artistic elements we employed.

We did have one huge setback with the film. Tim had envisioned a 3D animation opening, and we spent time (and money) on the creation and/or purchase of 3D models to render a fly-through of Paris. We hired a series of animators, without success, and we had to give that up. We spent around $8000 in the process, sadly. But Tim created instead what looks like an old film/slide show to support the introductory narration, and it works.

Much of the music was composed by Eric Harper of Vancouver, who did a marvelous job of scoring certain segments, especially the re-enactment scenes. Other musicians contributed their work— Lisa Haese Smith, Mea Karvonen, Elika Mahony, Malcolm Dedman and Nancy Lee Harper. An incredible vocal piece by Lucie Dubé is paired with our credit sequence, which we hope viewers will watch to the end. We also used a stock music library. Eric Johnson of Trailblazer Studios helped with the final audio mix in both languages.

All in all, there were many elements to create and tweak, including vintage photo enhancement, and a far-flung team who helped us.

What was something you learned in the process of creating this film?

First of all, we learned that foreign language production is not our strength, and the French language especially has nuances that French speakers don’t always agree on. So, we had an international team of assistants who advised us on the interview and script translations, and this took quite a bit of time and involved some angst. However, we had decided to tackle making a French version of the film, so with the help of French, Canadian, Australian, Belgian, and American collaborators, we managed to do it.

Neither version of the film will ever be perfect, but we made the best film(s) we could. Interestingly, where we had bi-lingual performers, we often enjoyed their performance in French over the English! One of these, Sheriff Osni, is a French chef at the school where I teach. He, like others who weren’t Baha’is, was moved to be part of the project.

Pierre Tremblay, who lives near Montreal, recorded most of the French voices, and we needed to utilize the services of Colin Ruhe in Costa Rica to do a few pick-up lines with our French narrator, Ophélie Welldon, who had moved there from Canada during the filmmaking. We had to rely heavily on French experts.

Working with one’s spouse can be hard. We have different working methods and timing. I don’t know if we’ll ever learn how to work together well, but somehow we manage to get through large projects—only because we both have a strong commitment to them. I think some marriage counselling might be needed if we tackle another one!

But largely what we learned was about the story itself. We found that Americans, including ourselves, know little about the European story and it was a great joy to discover so many wonderful things about it. Of course, the German, British, Austrian, and Hungarian friends may wish we had included the story of their countries as well—but it was quite enough for us to focus on one country for this film project.

I understand this film was made in collaboration with Spring Green Films. Would you like to share a little about that?

Yes, our friend Steve Jackson approached Steve Sarowitz of Spring Green, to see if he might be interested in helping us. Steve asked Ford Bowers and Maia Reneau to meet with us on behalf of the company. They were aware of our previous work and were receptive to offering support for part of the post-production costs. They were able to give us about a third of our total budget. In turn, we used their logo and designated them as “executive producers.” This is generally a title that implies monetary support without hands-on collaboration. It was great to have someone believe in us and offer support.

FUNDING is a major challenge for independent filmmakers. We also raised money through an IndieGoGo campaign and contributions through our Baha’i Assembly. Many people contributed their time and talents and funds sacrificially. One friend, Muhammad Ali Mazidi, was extremely generous and helpful to us, and arranged for us to do a Zoom “fundraiser” at one point. He died before the film could be completed, and we feel indebted to him and his contributions and encouragement. So, we dedicated the film to him.

What are your plans now that the film is released?

We hope to travel and screen the film in various places, as there is nothing quite like bringing a live audience together. Our premiere theatrical screening in Dallas was a thrilling success. We will be going to Austin and hope to do a screening in the Chicago area and also in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto. Maybe even France—but we’d need to do more fundraising for that.

We have also been approached to do some Zoom screenings with Q & A at the end. We still need to make a few DVDs for our IndieGoGo supporters. And we have so many people to thank for their contributions to the film!

Do you have any future projects planned?

Not yet. We need to recover from this one. Both Tim and I have other artistic endeavours we wish to pursue. But who knows about the future?

What advice might you have for emerging Baha’i filmmakers?

Don’t give up on your dreams. Build a team to support them, ask for help, launch crowd-funding ventures, call upon divine assistance, and give yourself to the creative process. Realize that projects of value take time and often require sacrifice. Even if it seems that the community may not be interested in your project(s), assume that your creative efforts will matter and that you are making history when you align your art with spiritual endeavors. Strive to continue to develop your art and craft, be supportive and encouraging of others, and let go of discouragement. There may never be enough time or money but pursue your work anyway. Trust your heart—if you are inspired, there must be a reason. In the world of the creative arts, much can be achieved to reflect the spirit of the Faith, and in time, this will cause the arts to “spread like wildfire,” as Shoghi Effendi predicts. His thoughts on the subject should give all of us ample reason to develop and utilize our talents:

“The day will come when the Cause will spread like wildfire when its spirit and teachings will be presented on the stage or in art and literature as a whole. Art can better awaken such noble sentiments than cold rationalizing, especially among the mass of the people.

We have to wait only a few years to see how the spirit breathed by Baha’u’llah will find expression in the work of the artists. What you and some other Baha’is are attempting are only faint rays that precede the effulgent light of a glorious morn. We cannot yet value the part the Cause is destined to play in the life of society. We have to give it time. The material this spirit has to mould is too crude and unworthy, but it will at last give way and the Cause of Bahá’u’lláh will reveal itself in its full splendour.” – Shoghi Effendi (10 October 1932, to an individual)

We can also turn to the Master for constant affirmation and encouragement: “Rejoice and be glad that this day has dawned, try to realize its power, for it is indeed wonderful!” —Abdu’l-Baha, Paris Talks, p. 68

Thank you, Anne, for taking the time to share this with us!

You can watch the video on YouTube in English, as well as in French. A behind-the-scenes video has also been created.

"*" indicates required fields

We recognise their continuing connection to land, waters and community. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their cultures; and to elders both past and present.

The views expressed in our content reflect individual perspectives and do not represent authoritative views of the Baha’i Faith.

Visit the site of the

Australian Baha’i Community

and the Baha’i Faith Worldwide

Notifications